Are dolphin rescues worth the effort?

Say you see a dolphin. And something just doesn’t seem right. It is swimming oddly. You take a photo, zoom in on the image and the reason becomes clear. There is a fishing leader wrapped tightly around the tail of the animal and the other end of the line is a tangle attached to the dorsal fin. The entanglement is limiting his range of movement.

Monofilament line cuts deeply into the dorsal fin of Ariel, a young dolphin that lives near Marco Island

The first thing you do (after a bit of Googling) is give a call to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Wildlife Alert Hotline: (888) 404 – 3922.

If you have a decent photo, it could prove helpful. Veterinarians will evaluate that photo to determine whether or not the entanglement threatens the life of the animal.

If it does look like the entanglement will result in the death of the animal if nothing is done then Blair Maise-Guthrie, the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program Coordinator with NOAA Fisheries, will put the regional Marine Mammal Stranding Network on alert. In Florida, this is a network of organizations – Mote Marine in Sarasota, Harbor Branch Oceanographic institute, University of Florida, Sea World, Clearwater Marine Aquarium to name a few – that will contribute trained personnel and resources such as boats, floating platforms, nets and medical supplies to the rescue effort. After consultation a preliminary date will be set for the intervention.

There may be delays. If a week passes with no further sightings of the animal in the area, the rescue will be postponed. If the weather turns windy or stormy the date may be pushed back again.

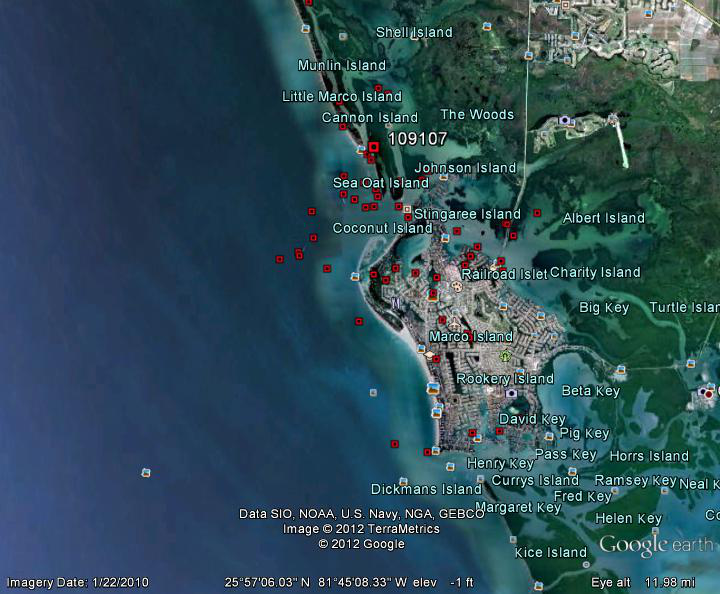

But if the stars align, the team will gather in the early morning near where the troubled animal was last seen. A common radio channel will be agreed upon and boats will fan out searching. Hours may pass – the dolphin could be behind any one of a number of islands, milling around in one of the hundreds of canals.

And then someone will spot her. The call will go out and all of the boats will gather, hanging back as a lead boat slowly tracks the dolphin from a distance until it swims into an area of unobstructed shallow water.

The capture boat positioning to set the net during the intervention to disentangle Seymour in March, 2012

Nothing is guaranteed at this point. The imperiled dolphin may not be in an area that allows for a capture – too deep, too narrow to deploy a net. It may be in a group of six other dolphins preventing its capture.

But if everything falls into place the call is made and suddenly the capture vessel ( a repurposed mullet fishing boat with the engine mounted forward of the stern to allow deployment of a net) surges forward throwing up a wake as it reels out the net in a circle around the dolphin. The net is gathered, trained volunteers jump in the water and eventually the animal is in hand (or hands rather).

Standing in waist deep water veterinarians work to remove the monofilament line. The vital health statistics of the animal are recorded. If necessary, antibiotics are administered. Before release, scientists from Mote Marine will affix either a satellite-linked tracking device or a yellow tag to the dolphins dorsal fin.

If the animal is healthy, that is it – he or she is released and everyone goes home feeling good. In other cases the animal may have injuries that require a period of rehabilitation in a facility before release. Mission accomplished, right? I have been involved in several of these operations now and that is certainly the feeling – all of the anxiety or concern you felt for the animal recedes and everything feels right in the world for a moment.

Seymour is prepared for release after successful removal of the fishing line embedded in his tail.

But is everything alright? How long did that dolphin survive after the intervention? Did it resume its normal life as a member of the local community of dolphins. If it was a female did it live long enough to reproduce and add to the viability of the population? Was everything really alright or did we turn our attention away too quickly?

These are the question that Katie McHugh, a staff scientist employed by the Chicago Zoological Society and based at Mote Marine Laboratory as part of The Sarasota Dolphin Research Program sought to answer in her original research article “Staying Alive: Long-term success of bottlenose dolphin interventions in southwest Florida” recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

And this is the point of the satellite-linked tracking device or the yellow tag – to facilitate post intervention monitoring of the animal to at least be able to evaluate the short to medium term success of the intervention.

Dr. McHugh was able to use data from post intervention tracking and follow up observation of 27 bottlenose dolphin interventions between 1985 and 2019 in her analysis.

Skipper fitted with a yellow tag to facilitate post-intervention monitoring.

The question of the long-term fate of dolphins that are the subject of interventions is important because funds available for conservation efforts are limited. Operations involving the capture and release of wild dolphins are expensive, time consuming and logistically very difficult.

I was able to contribute to the paper by providing extensive sighting data on two dolphins that were the subject of interventions near Naples and Marco Island and individual sightings of two others whose range fell within The Dolphin Study’s study area from a database of sightings I have maintained since 2006.

In the case of the two interventions near Marco Island the answer to Dr. McHugh’s questions about their long-term benefits is mixed.

In March 2012, the stranding network launched an intervention to capture and release a sub-adult male dolphin named Seymour that was photographed with monofilament fishing line tightly wrapped and embedded in his tail near the fluke. Scar tissue was building up around the wound and, when we encountered him during surveys, Seymour appeared distressed, repeatedly slapping his tail on the surface of the water. The initial effort to capture and treat Seymour was a success but he was observed for only six months after the intervention.

Deeply embedded monofilament fishing line produces scar tissue on Seymour’s tail.

A satellite-linked tag is affixed to Seymour’s dorsal fin prior to release.

The long-term outcome of a September 2014, capture and release of a young female dolphin named Skipper (who, like her older brother Seymour, managed to run afoul of recreational fishing gear) was much better. Skipper, a calf at the time of her rescue, is still alive today, living in her normal range, fully integrated into the community and approaching maturity herself. I saw Skipper the other day in the heart of her range socializing with her brother, older sister and nephew. Skipper is 7 and a half years old now and, if her luck holds, will likely become a mother herself soon. The lifesaving intervention by the stranding network not only saved skipper’s life but also contributed to the viability of the population.

Skipper’s entanglement was removed before it became deeply embedded.

2-6-2020: Skipper is sighted socializing with seven other dolphins

But these are anecdotes.

In order to answer the question of the value of interventions more definitively. Dr. McHugh examined evidence from 27 bottlenose dolphin interventions between 1985 and 2019 where there was enough long term follow up monitoring to shed some light on those questions she was seeking to answer. Many of the rescues occurred near Sarasota and she could draw from data collected on what is probably the most fully documented population of bottlenose dolphins in the world. Since the 1970’s Researchers at the Sarasota Dolphin Research Project have conducted regular photo-identification surveys of the resident dolphin community there.

Post intervention tracking data from Seymour’s tag provided by Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program.

In evaluating these interventions, Dr. McHugh identified 4 criteria for success:

- Survival: How long did the animal live post intervention?

- Ranging patterns: Did the dolphin remain in the community range from where they were rescued?

- Absence of abnormal behaviors post release: Here she was particularly concerned with whether the dolphins were involved in begging for food from humans or “patrolling, scavenging or depredating from active fishing gear” – the sorts of behaviors that could lead to another entanglement.

- Reproduction: Did adult females or females that became sexually mature post intervention produce calves?

She also employed a variety of statistical devices to analyze the association patterns of the animals pre- and post-intervention and to model the population level impact of the rescued females who would go on to produce calves.

Skipper enjoying a lazy morning with her older sister, Kaya, now a young mother.

The goal of wildlife rescues is to help animals remain in or return to wild populations to survive and reproduce. Dr. Katie McHugh concluded that her retrospective analysis of these 27 interventions conducted over a thirty-five-year period demonstrated the potential for achieving long term success at this primary goal.

Approximately 75% of rescued dolphins survived over multiple years, all living animals remained in their local communities, and all sexually mature females have successfully reproduced in those communities. Together these findings strongly support the idea that interventions to save animals with life-threatening anthropogenic injuries provide benefits not only to the welfare of those individuals, but also to the stability and growth potential of their local populations.

She noted, however, that not all interventions are successful, and “Even rescues that appear to be short-term successes can result in unexpected failure years later if animals face lingering impacts from their injuries”.

Perhaps that was the case with Seymour. When first we photographed him, the fishing line was already deeply embedded in his tail and producing a lot of scar tissue and it was an additional 3 months before a rescue could be carried out.

Though only two of the reviewed interventions ended in failure “an additional five individuals failed to survive a full year post-intervention bringing the overall long-term survival success rate to 74%.”

For this reason, the authors write that while rescues are a “useful last resort” management strategy for wild bottlenose dolphin population should focus on preventing situations that lead to a need for interventions. Rescue entangled dolphins yes, but better to prevent the entanglement in the first place.

Dolphins shadow a recreational fishing boat looking for an easy meal.

Some years ago Kim Bassos-Hull, a Research Associate with the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program and a Senior Biologist with Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida was working with fishermen and others to address problematic interaction between dolphins and recreational fisheries – things like dolphin’s shadowing fishing boats and stealing fish. These are the sorts of abnormal behaviors that end up with dolphins either entangled in monofilament line or ingesting fishing gear. Chris Desmond and I helped facilitate a meeting between Kim and some of our local charter captains to get their perspective and brainstorm solutions.

Here are some strategies that came out of their efforts.

We will always be grateful for the lifesaving assistance the folks at Mote marine and The Sarasota Dolphin Research Project provided to the dolphins in our community as key members of The Marine Mammal Stranding Network. For that reason it was an honor to be able to contribute to this research paper as Dr. McCugh sought to further our knowledge of the efficacy of the capture and release efforts.

Be sure to visit the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program’s website to learn more about their research and rescue efforts.

And read “Staying Alive: Long-term success of bottlenose dolphin interventions in southwest Florida” here.

Skipper today: her yellow tag is gone and a slight indent is visible on her tail where the monofilament line had started to become embedded pre-intervention.

Here at The Dolphin study, we are still keeping tabs on Skipper, one of the subjects of this study. The story of the long-term impact of the intervention to free her from fishing line is still being written. Will she live long enough to reproduce? How many calves will she have? Go here for an in depth look at Skipper’s social life since the rescue. And visit her profile in the database here to view her range, evaluate her association patterns and see her most recent sightings.